The Rolling Stones: that 50-year itch

As the Rolling Stones' pivotal 1978 album Some Girls is reissued, Messrs Jagger, Richards, Wood and Watts talk about sex, drugs and survival – and the chance of a celebration tour

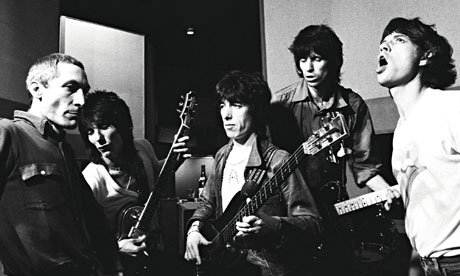

The Rolling Stones in 1978. From left: Charlie Watts, Ronnie Wood, Bill Wyman, Keith Richards and Mick Jagger. Photograph: Helmut Newton

The Rolling Stones in 1978. From left: Charlie Watts, Ronnie Wood, Bill Wyman, Keith Richards and Mick Jagger. Photograph: Helmut Newton Ronnie Wood, wizen-faced survivor of rock'n'roll excess, is sipping daintily on a glass of coconut water. "Love it, 100%," he says, his leg jiggling with enthusiasm so that the ice cubes in the white liquid clink as he talks. "Little taste of holiday, right there." Wood laughs throatily. "I drink so much coffee, this helps balance me out."

When a Rolling Stone admits that coffee is his greatest vice, you know times have changed. During his time as guitarist for the band, Wood estimates he's burned through £20m on drugs and alcohol. His bandmates didn't think this was particularly exceptional. Keith Richards, after all, used to indulge in speedballs of cocaine and heroin with such regularity that he cheerily referred to the toxic cocktail as "the breakfast of champions".

But nowadays things are rather different. The Stones have all grown up – Wood, at 64, is the youngest in the band; drummer Charlie Watts the eldest at 70 – and, despite hovering perilously around retirement age, they are still working. This month sees the release of a re-mastered version of their hit 1978 album Some Girls, including new tracks unearthed from the archives by producer Don Was. The expanded album will also feature a previously unseen Helmut Newton photo session from the time, depicting the band in a series of moody rock'n'roll poses – all cheekbones and pouty insouciance.

Today, when I meet Wood in the upholstered plushness of a central London hotel, he looks essentially the same as he did three decades ago – a bit more weather-beaten, perhaps, but still sporting an identical Worzel Gummidge hairstyle and spray-on skinny jeans that seem to have been beamed in directly from the 1970s. Does it feel surreal looking back to those photographs now?

"Yeah," he says. "It doesn't seem like it's been all those years. What is it, 30?"

Thirty-three.

He gapes in mock horror. "The 80s only seem like yesterday to me. The 90s went so fast. Before you know it, time has flown by."

In their time as the world's most famous rock band, the Rolling Stones have sold more than 200m albums and released eight number one singles. When they took to the road to promote their 2005 A Bigger Bang album, it became the highest-grossing tour of all time (since bettered by U2's 360˚ tour of 2009-11) – at one concert alone, on Copacabana beach, 1.5 million people turned up to watch them live.

As a band, they have swaggered their way through the decades: a multi-headed, hard-partying, hard-living, rock'n'roll beast that hoovered up drugs, bedded glamorous women and all the while managed to produce some of the finest popular music of the 20th century, including "Wild Horses", "Jumpin' Jack Flash", "Gimme Shelter", "Brown Sugar", "Satisfaction", "Paint it Black" and "Sympathy for the Devil". And they're still going.

"In a way, they are the template for every rock band that's come along in the last 40 years," says Philip Norman, the author of a biography of the Rolling Stones and one of Mick Jagger, which is coming out next year. "It seems very weird they've lasted so long because for years and years, all through the 60s, they were the most unstable of any band out there. I think their longevity is due to this incredible image that was given to them, of being wicked, of sex, drugs and rock'n'roll. It's extraordinary that it's stuck… These men are now getting on for 70 and they're still exciting for terribly young kids. They are the first old white musicians ever to be cool."

But arguably the Stones' greatest achievement is the simple fact of their survival. Next year, the band marks its 50th anniversary, a feat of longevity that seems all the more remarkable in the face of their seemingly hell-bent desire to kill themselves. Keith Richards, for one, only gave up cocaine in 2006 after falling out of a tree in Fiji and undergoing surgery for a blood clot on his brain. When I speak to him over the phone from his home in Los Angeles, the 67-year-old is sanguine about cleaning up his act.

"Everybody's got to grow up eventually," Richards says in a dry voice that sounds oddly like Bill Nighy's impersonation of an ageing rock star in the film Love Actually. "All of my stuff, I considered it all an experiment that went on too long." Does he miss the drugs? "No, darling. Once you've sniffed it, you've sniffed it."

At 68, Mick Jagger, to whom I also speak over the phone, is less forthcoming. Does he have any regrets? "You're not honestly asking that question, are you?" he says, snorting. "I can't possibly answer that."

Back in the hotel room, drinking his coconut water, Wood gives an impish grin when I ask if he feels like a survivor. "Yeah, definitely," he says, nodding his head vigorously. "Yeah, I've seen all the people dropping like flies over the years and it makes me realise how lucky I am."

The re-release of Some Girls is especially poignant for Wood because the album marked the first time he was officially recognised as a member of the band – "I felt I was finally home," he says. Although the Rolling Stones were formed in 1962 by Jagger and Richards (who were at primary school together), they have, like a particularly prolonged game of consequences, undergone a series of personnel changes over the years. Guitarist Brian Jones, one of the original lineup, drowned in his swimming pool in 1969. Mick Taylor took his place, before eventually being replaced by Wood, while bassist Bill Wyman retired from the Stones in 1992.

Before the release of Some Girls, the band was undergoing something of an identity crisis. The freewheeling optimism of the 1960s had given way to the drug-addled reality of the 1970s and they were battered and bruised from 16 years on the road. There had been the notorious Redlands bust in 1967, after which Jagger and Richards had been jailed for possession of cannabis and amphetamines, famously prompting William Rees-Mogg to ask: "Who breaks a butterfly on a wheel?" in a Times editorial. Two years later, during a Stones performance at a rock concert in Altamont, California, an 18-year-old fan was murdered by a group of Hell's Angels.

Then, just as the band were about to start recording in early 1977, Richards was arrested for heroin possession in Toronto, where the Stones had been touring, leading to the very real possibility that he might be sent to jail for years and the album would never be made.

"Oh yeah, I was under several indictments dotted all over the globe," says Richards with customary laconicism when reminded of this. "But that was just my day-to-day life."

When I meet Charlie Watts, he remembers it as being a "pretty serious" situation. To complicate matters, Wood was simultaneously having an affair with Margaret Trudeau, wife of the then Canadian prime minister. "It was a bit worrying," says Watts, a thoughtful wrinkle appearing on his brow.

In the end, Richards got away with a light sentence in return for promising to perform a charity show for the Canadian National Institute of the Blind (which took place in 1979). Partly in celebration at this second lease of life and newfound charitable impulse, Richards reinstated the "s" at the end of his surname, which had disappeared after a former manager deemed it wasn't rock'n'roll enough.

"I just thought, you know, I'm not Cliff Richard, and that's for sure," says Richards with a guttural laugh. Down the crackly phone line, it sounds like sandpaper being scraped against a pebbledash wall.

With Richards a free man once more, the band traipsed off in varying states of health and sobriety to Paris to record the album in a small studio in Boulogne-Billancourt. According to Jagger, the fact that they were all living and working together over a sustained period meant that "one of the good things about the record is this unity – it was all done in Paris in a relatively short space of time. There were a lot of Keith problems but once we were in there, it was pretty concentrated."

There was also a sense in which the Rolling Stones wanted to prove they were still relevant. At the time, their brand of rhythm-and-blues soul music was in danger of seeming outdated in comparison with the raw, stripped-back anger of punk or the frenetic energy of disco.

"The punks had given us a kick up the ass," says Richards. "Or let's say 'arse' as it's England. It felt like we'd been sitting on our laurels for a couple of years. There'd been the Sex Pistols, the punk movement. We wanted to strip the band down so there weren't a lot of horns or extra musicians… We decided to keep it strictly guitar."

The result was a series of songs marked by thumping guitar riffs and a moody dance beat, the most famous of which – "Miss You" – reached number one in America. The album went six times platinum in the US and garnered an extremely positive critical response.

In fact, the Some Girls tour in 1978 produced some of the most electrifying live performances of the Stones' careers – a DVD featuring unseen footage of the band playing a tour date in Fort Worth, Texas, will be released later this month and shows Jagger at the top of his game, strutting across the stage like a demented cockerel.

"I started off thinking about what being a performer meant when I was about 16," says Jagger when I ask him about the tour. "I hope I'm not being immodest, but I realised I would go out and do it, and the more people seemed to like it the more I seemed to do stupid things and dance. You sort of realise that's your fate and you develop it."

Does he think he's a good dancer?

"Not really. I do my best but really it's about song interpretation, being the character of the song…It's about keeping the audience enthused, keeping them involved. They don't come to see a dancer par excellence."

The album had its quieter moments too, most in evidence on the bluesy "Beast of Burden". Richards has, in the past, said he wrote the track as an apologetic acknowledgement of all the difficulties his drug problems had caused Mick Jagger.

"Actually, if anything, I was trying to say sorry to Mick for passing on the weight of running this band," Richards says now. "We were at the stage where we were getting bigger. The whole music business was getting bigger, and I was basically trying to say to Mick: 'You don't have to do it on your own.'"

Did Jagger listen? Richards erupts. "No. He very rarely does. That's why I love him."

Apart from the music, the partying and the trail of beautiful women, perhaps the most fundamental reason for the enduring public fascination with the Rolling Stones is the friction surrounding its central creative partnership. Jagger and Richards seem forever locked in an epic battle between love and hate, admiration and mistrust, that has twisted and turned throughout the last half century like the rock'n'roll equivalent of the naked wrestling scene in Women in Love.

Is it, I ask Richards, a bit like working with your brother? "No, it's like working with Maria Callas," he shoots back. "The diva is right and we've got to try and put music together without annoying the diva. If the diva gets too annoyed, then I get pissed off. Do you think when we get together we're all like happy families? Forget about it. We've been fighting cats and dogs all our career.

"We're like brothers in that sometimes we love each other and sometimes we hate each other and sometimes we don't even care. I've been playing guitar, watching that bum [dance in front of me] for years."

Relations between the two, always fractious, probably weren't helped by the publication last year of Richards's rollicking autobiography, Life, in which he claimed – among other things – that Jagger was "unbearable" and in possession of "a tiny todger… he's got an enormous pair of balls – but it doesn't quite fill the gap".

I have been told by the PR that I'm not allowed to ask about "big and small willies", which is the only time genitalia size has been listed as a verboten topic in any interview I've ever done. Still, how are things with Mick now?

"Oh fine," says Richards. "We're OK."

"We don't squabble very much to be honest," Jagger says.

I don't have the balls to ask Jagger about… well… the balls, given that he can barely conceal his disdain for some of my questions. When I have the temerity to ask him about how he squared his anti-establishment reputation with accepting a knighthood in 2003, Jagger replies: "It's a bit old hat as a question, if you don't mind me saying. It was quite a long time ago. I think if you're offered these things, if you refuse it's almost like a parody of being a rebel in a way. If you insist on using your title, then it's really silly. It's almost, in our sort of society, rude to turn things down and silly to take them seriously. As Confucius said: 'All honours are false.'"

Is there any other rock star on the planet who could get away with quoting Confucius? Probably not. Somewhere, on the other side of the Atlantic, Keith Richards is probably rolling his eyes.

The unpredictable dynamic between Richards and Jagger means that, like the children of perpetually squabbling parents, Ronnie Wood and Charlie Watts have tended to get caught in the middle. Thirty-three years on from the release of Some Girls, they both have different approaches for dealing with the fall-outs. Watts, who has been married for 47 years and doesn't consider himself a rock star, retreats to his wife Shirley's stud farm in Devon when things get too heated.

"I've never been enamoured of rock'n'roll," he says, smoothing down the trouser legs of his impeccably cut three-piece suit. "I mean, I love going on stage and people clapping but I never believed anything outside that." There is a long pause. "It felt a bit minor to me, the whole thing. It's never impressed me that much."

Wood, by contrast, is frequently cast as peacemaker. "I can't see people angry or holding something against each other," Wood says. "I have to bring it out in the open and say: 'You've got to patch this up, you guys.'"

Like all of them, Wood's dedication to the band and the lifestyle it embodied has come at some personal cost. In 2008, he left his second wife, Jo, generally seen as a stabilising influence, for a Russian cocktail waitress called Ekaterina Ivanova. Their four children were devastated by the split. Wood began drinking again and was arrested a year later after witnesses claimed he tried to throttle his girlfriend during a drunken row in the street. He went into rehab for the eighth time and has now been sober for almost two years.

"I became an annoying kind of drunk," Wood recalls. "I annoyed myself and it wasn't working any more… I thought, 'This is not me, this is horrible.'

"I would have long times – months – of sobriety and then say, 'I've got it, I can have a drink now, I can have a drug now' and it would all explode and go terribly wrong… I'm still learning from my mistakes and I'm determined I'll never do anything stupid like that again."

Does he feel his age? "No, I think that's something that saves me. I still feel 29. Maybe I should act my age more, but I just can't."

These days, Wood is contentedly single (after a brief relationship with Brazilian model Ana Araújo) and concentrating on his art – a solo show of his charcoal portraits and oil paintings opened earlier this month. Watts, meanwhile, is much in demand as a jazz drummer after having survived a battle with throat cancer seven years ago. Jagger has formed a new band, SuperHeavy, with singer Joss Stone and Eurythmics founder Dave Stewart, and continues to produce films through his own production company. Richards, the former hellraiser-in-chief, is married to former model Patti Hansen with whom he has two daughters. Nowadays, Richards tells me: "The best drug is breathing." Pause. "I mean, heroin is fantastic. Until you've had too much of it and then you're likely to be dead."

But despite the fact that they are all happily settled and doing their own thing, there is an undeniable frisson when the question of a Rolling Stones reunion is mooted, as if none of them can quite let go of the excitement that comes from being in the band.

Wood says he's having a long overdue operation next month to fix a cracked bone in his foot "so I'm ready for action next year just in case". In case of a tour? "Fifty years!" he shrieks. "It's got to be done."

Watts is, characteristically, more circumspect. "I would like to think we'd do a tour. Um, if we don't, we don't. I mean, I've felt like that for the last 50 years. It's never bothered me if the Rolling Stones stopped tomorrow."

Jagger gives me predictably short shrift. "I've no idea," he sniffs. "We don't really get together that much as a group."

And what about Richards? Can he envisage a reunion tour? "Envisage?" he guffaws. "Yeah. I dream of it."

Some Girls is out on 21 November on Universal; a companion DVD, Some Girls Live in Texas 1978, is released the same day on Eagle Rock